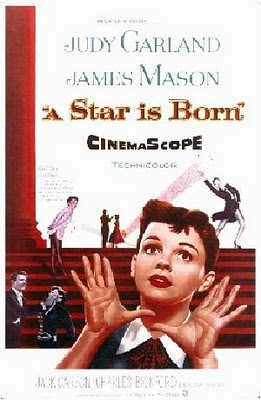

A new star is born consuming the detritus surrounding its burning aura, sustained by its own internal pressure. Director George Cukor’s Hollywood fable is as flammable as camphor and nitrate, revealing lives preserved in negative, cast upon the silver screen.

A caustic view behind the glitz and glamour, Cukor’s film has become one of the most damning purges of Hollywood where stars sometime just burn slowly away, gone and forgotten, the nuclear fusion of box office all that matters. James Mason portrays the aging actor Norman Maine, his blood alcohol level reaching mythic proportions. He nurtures a young nightclub singer named Esther Blodgett and gives her a chance to make it Big. She is soon transformed into Vicki Lester but retains the kindness and compassion intrinsic to her nature, unlike Norman who is a drunken and spoiled actor who may have once been a nice guy…once upon a time. Esther falls in love with her mentor but he remains a stranger: when they are married before the Justice of the Peace, Norman’s true name is revealed and Esther suddenly realizes that she doesn’t really know this man. But she gives it her all, sacrificing her career to keep her vows.

James Mason plays the perfect drunk, inebriated with liquid toxins and power, imbuing Norman with a spoiled angst that doesn’t quite diminish his soft spoken demeanor: he’s a jerk but not completely unlikable. Judy Garland as Esther is a bit too old for the part and looks as if she has a few years of benders under her belt, but her genial femininity and charm make the heart skip a beat or two, and her crying jags so full of emotional frisson the illusion is sustained. The film is padded with a few too many songs that showcase Garland’s outstanding vocal range, and it’s not until the third act that she really gets to perform dramatically. The songs are diagetic, contained within the story, except the Honeymoon suite which starts a capella before an off-screen orchestra joins in.

A STAR IS BORN is about the rise and fall of two Hollywood stars, but it’s also about the loss of male potency at a time when women where still considered subordinate. As Norman drinks himself towards oblivion, he cannot stand the fact of being supported by his wife: instead of helping her, he unconsciously attempts to destroy her. But in a sobered state, he makes the absolute sacrifice for his wife. And Esther’s final words subjugate her own identity to become Mrs. Norman Maine.

Final Grade: (B+)

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Sunday, September 19, 2010

THE MIRROR (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1975, Soviet Union)

Childhood memories through the dark refraction of still waters, regrets and reflections upon a life passing away towards the unknown. Andrei Tarkovsky’s conceit becomes a universal human experience, shared emotions that run deep like roots into the damp earth of the soul, and exhale as a breath upon waves of grass, guilt burned away, an entropic elemental estuary that leads to salvation.

THE MIRROR is about nothing, a disassociated cinematic plot flowing like mercury poisonous yet beautiful, and yet it is about everything engendered in the human condition. Tarkovsky utilizes newsreel footage of the Great Patriotic War and places the characters in a historical context of displacement and dysfunction. Time becomes fluid as rainwater, a ubiquitous imagery that floods the narrative, seeping through the cracked reminiscence bringing both life and destruction. The film is not only a dying man’s dream, an honest illusory past but a mirror of spectatorship that actively involves the audience at an emotional and spiritual level, sublime and subjective, a participatory projection of introspection.

Tarkovsky’s clever structure becomes a surreal journey denying logical dramatic form, tripping through the looking glass and beyond the confines of cinematic compositions. An elegy that illuminates the dark night of our souls, life is always worth living. So live.

Final Grade: (A)

Thursday, September 16, 2010

VIOLENCE AT NOON (Nagisa Oshima, 1966, Japan)

A commune’s philosophy of free love spreads a societal canker, a nihilistic avatar sheathed in human clothing who sates his libidinous needs with violent penetration. Nagisa Oshima condemns the anti-establishment as their worldview romanticizes utopia while blinded to the hungry wolf in the fold.

Oshima begins the story with a violent rape and murder, building expectations towards a standard crime drama thriller. But it soon becomes apparent that the film is much more rebellious, a penetrating social and emotional allegory concerning two women, where criminal justice and social hierarchy battle for supremacy in a world gone sour. Oshima’s style is as visually stunning as Kurosawa’s RASHOMON, embedded with hundreds of cuts to sweaty close-ups revealing paranoid eyes, reality interpreted like electrical impulses charged upon a damaged psyche. The Cinemascope compositions often separate characters by a vast gulf of indifference, or brings them together in a choking embrace, an eclipse of flesh, blood, and bone: a journey to the dark side of the soul.

Shino becomes the first victim in the film (though not the rapist’s first crime) and it’s obvious that the two share a common past. She is unaware of his intent but falls prey to his tempestuous prayer, penitent upon the alter of sexual abuse. Oshima focuses on emotional relationships and not the physical act, conjoining Shino and the criminal’s wife Matsuko like binary stars, their gravitational pull both keeping balance and slowly tearing them to shreds. Shino carries the burden of survivor’s guilt, and the knowledge that she owes her life to this despicable man. But her knowledge is limited: after attempting suicide years before, Shino believes he saved her life before ravaging her virginity (he explains, she was dead so it isn’t rape to fuck a corpse). But Oshima reveals that the rope fortuitously broke, she would have survived anyway, so another moral splinter occludes the narrative.

Matsuko’s guilt concerns her spurning the commune’s leader, whose response is to enter a dual suicide pact with Shino: as his life fades to black, he is the only witness to Shino’s assault. Matsuko must also decide that if she admits her husband is the Noontime Rapist, then her whole belief in the inherent goodness of human nature is flawed, that life is not (and never was) as she knew it. What should be an easy decision for the two women to go to the police and help solve this crime spree becomes a spiritual civil war leading to self-destruction, ignoring reality to grasp the ethereal bonds of delusion. Bob Dylan was right: the human maggots that infest Maggie’s farm would have been proud.

Final Grade: (A)

Oshima begins the story with a violent rape and murder, building expectations towards a standard crime drama thriller. But it soon becomes apparent that the film is much more rebellious, a penetrating social and emotional allegory concerning two women, where criminal justice and social hierarchy battle for supremacy in a world gone sour. Oshima’s style is as visually stunning as Kurosawa’s RASHOMON, embedded with hundreds of cuts to sweaty close-ups revealing paranoid eyes, reality interpreted like electrical impulses charged upon a damaged psyche. The Cinemascope compositions often separate characters by a vast gulf of indifference, or brings them together in a choking embrace, an eclipse of flesh, blood, and bone: a journey to the dark side of the soul.

Shino becomes the first victim in the film (though not the rapist’s first crime) and it’s obvious that the two share a common past. She is unaware of his intent but falls prey to his tempestuous prayer, penitent upon the alter of sexual abuse. Oshima focuses on emotional relationships and not the physical act, conjoining Shino and the criminal’s wife Matsuko like binary stars, their gravitational pull both keeping balance and slowly tearing them to shreds. Shino carries the burden of survivor’s guilt, and the knowledge that she owes her life to this despicable man. But her knowledge is limited: after attempting suicide years before, Shino believes he saved her life before ravaging her virginity (he explains, she was dead so it isn’t rape to fuck a corpse). But Oshima reveals that the rope fortuitously broke, she would have survived anyway, so another moral splinter occludes the narrative.

Matsuko’s guilt concerns her spurning the commune’s leader, whose response is to enter a dual suicide pact with Shino: as his life fades to black, he is the only witness to Shino’s assault. Matsuko must also decide that if she admits her husband is the Noontime Rapist, then her whole belief in the inherent goodness of human nature is flawed, that life is not (and never was) as she knew it. What should be an easy decision for the two women to go to the police and help solve this crime spree becomes a spiritual civil war leading to self-destruction, ignoring reality to grasp the ethereal bonds of delusion. Bob Dylan was right: the human maggots that infest Maggie’s farm would have been proud.

Final Grade: (A)

Sunday, September 12, 2010

THE PLEASURES OF THE FLESH (Nagisa Oshima, 1965, Japan)

A man is caught in a conspiracy of justice, divorced from reality, his life as transient as a suitcase full of stolen money. Director Nagisa Oshima’s film noir plot whose is a destination mirrored in destructive impulses, a character study of a man denied his obsession, his kamikaze life spiraling towards self-fulfilling prophecy.

The opening shot is a surreal perception of a young bride, running through the crowd to embrace a shadow, a nightmare in slow motion. Suddenly, we realize this to be a fantasy and are catapulted backwards in time to the dreamer: a young teacher who has a Lolita-like crush on a student. The post-pubescent Shoko has a secret lurking in the dark recess of her mind (and libido), a shameful burden imposed upon her by a rapist who has come back to blackmail her. Wakizaka (our protagonist) delivers the ransom money to the bestial rapist, slathered in sweat from the ubiquitous heat, then pushes him from speeding train. But his crime is witnessed by another and soon Wakizaka is blackmailed, not for money, but to keep a cache of cash for an accountant who swindled public funds. So begins the downfall of a human being.

Oshima’s exemplary use of Cinemascope compositions is used to full effect, eclipsing characters to create a claustrophobic tension and often isolating action to the periphery, relegating people to the fringe. Often bright colors flare across the screen, like neon lights painted upon glass: a characteristic of Wong Kar-wai and Christopher Doyle’s style in modern films. Oshima’s narrative is also a tribute to B-movie crime dramas, allowing the story to revolve around genre conventions with gang leaders and knife fights, and the nihilistic denouement: everybody is guilty of something; jealousy, greed, murder, or sexual abandon (or all of the aforementioned!). Though Wakizaka is a flawed hero, he is not without the audience’s compassion and relegated to the status of victim, dividing the morality tale into fractions. Wakizaka’s ejaculatory purge strips him of his humanity when he needs it most, able to purchase sex but finding it impossible to purchase love.

Final Grade: (A)

The opening shot is a surreal perception of a young bride, running through the crowd to embrace a shadow, a nightmare in slow motion. Suddenly, we realize this to be a fantasy and are catapulted backwards in time to the dreamer: a young teacher who has a Lolita-like crush on a student. The post-pubescent Shoko has a secret lurking in the dark recess of her mind (and libido), a shameful burden imposed upon her by a rapist who has come back to blackmail her. Wakizaka (our protagonist) delivers the ransom money to the bestial rapist, slathered in sweat from the ubiquitous heat, then pushes him from speeding train. But his crime is witnessed by another and soon Wakizaka is blackmailed, not for money, but to keep a cache of cash for an accountant who swindled public funds. So begins the downfall of a human being.

Oshima’s exemplary use of Cinemascope compositions is used to full effect, eclipsing characters to create a claustrophobic tension and often isolating action to the periphery, relegating people to the fringe. Often bright colors flare across the screen, like neon lights painted upon glass: a characteristic of Wong Kar-wai and Christopher Doyle’s style in modern films. Oshima’s narrative is also a tribute to B-movie crime dramas, allowing the story to revolve around genre conventions with gang leaders and knife fights, and the nihilistic denouement: everybody is guilty of something; jealousy, greed, murder, or sexual abandon (or all of the aforementioned!). Though Wakizaka is a flawed hero, he is not without the audience’s compassion and relegated to the status of victim, dividing the morality tale into fractions. Wakizaka’s ejaculatory purge strips him of his humanity when he needs it most, able to purchase sex but finding it impossible to purchase love.

Final Grade: (A)

Monday, September 6, 2010

SUMMER HOURS (Olivier Assayas, 2008, France)

A Matriarch’s testament to her family is the eternal gift of love, like a memory of a dream half-forgotten then profoundly remembered, not locked in the hard value of objects diminished by emotional gravity.

Olivier Assayas’ familial dramaturgy at first seems a set piece for septic melodrama, where disparate siblings bicker and argue over heirlooms and inheritance, but it soon becomes apparent that this open ended narrative exceeds expectations. The characters live and breath outside the confines of the frame, dimensional and complex, each introduced but their intentions not readily understood. Assayas seems more interested in acceptance than rejection, as a family comes together but still retains a domestic democracy, living with decisions though not acutely agreeing with them. The plot doesn’t descend into a backstabbing foray of familial angst, where dark secrets taint siblings and manipulate compassion towards the director’s morality. Here, we must think for ourselves and SUMMER HOURS seems like a visit with an extended family, where we greet and offer heartfelt condolences, and suffer the loss of a parent in the ethereal jaunt of time.

The story is also about Art as a living product, inanimate and static when kept from human hands, like a valuable vase secreted away as a display piece while another serves a function, embracing flowers as an icon of remembrance, a centerpiece of love and memory. The rare furniture and artwork imprisoned by the museum loses its innate humanity, ignored by the churlish masses who wander briefly by. An apt metaphor for places and things that seem to hold childhood memories, forever lost to the ravages of entropy, but held eternally in the heart to be shared with others.

Final Grade: (B)

Olivier Assayas’ familial dramaturgy at first seems a set piece for septic melodrama, where disparate siblings bicker and argue over heirlooms and inheritance, but it soon becomes apparent that this open ended narrative exceeds expectations. The characters live and breath outside the confines of the frame, dimensional and complex, each introduced but their intentions not readily understood. Assayas seems more interested in acceptance than rejection, as a family comes together but still retains a domestic democracy, living with decisions though not acutely agreeing with them. The plot doesn’t descend into a backstabbing foray of familial angst, where dark secrets taint siblings and manipulate compassion towards the director’s morality. Here, we must think for ourselves and SUMMER HOURS seems like a visit with an extended family, where we greet and offer heartfelt condolences, and suffer the loss of a parent in the ethereal jaunt of time.

The story is also about Art as a living product, inanimate and static when kept from human hands, like a valuable vase secreted away as a display piece while another serves a function, embracing flowers as an icon of remembrance, a centerpiece of love and memory. The rare furniture and artwork imprisoned by the museum loses its innate humanity, ignored by the churlish masses who wander briefly by. An apt metaphor for places and things that seem to hold childhood memories, forever lost to the ravages of entropy, but held eternally in the heart to be shared with others.

Final Grade: (B)

Friday, September 3, 2010

STAGECOACH (John Ford, 1939, USA)

A disparate group of travelers must traverse dangerous ground to reach their mutual goal, fighting both themselves and Apaches along the way. John Ford’s epic Western accommodates nearly every genre trope before subjugating them, turning expectations upside-down as STAGECOACH becomes not a shoot’em-up excess but an exercise in Sociology.

Ford pulls focus to create a claustrophobic suspense between the characters, divided by their social graces (or lack thereof) and reputations. Dallas is a prostitute spurned by Lucy, pregnant with desire to visit her husband. Doc Boone’s soul is captured in a bottle of spirits, and he takes full advantage of Peacock the meek whiskey salesman. Hatfield is a rogue and gambler, offering his flirtatious protection to Lucy while the banker Gatewood jealously guards his suitcase and prejudices. Their fate clashes with the notorious Ringo Kid who surrenders uneventfully and forms a kinship with Dallas, the other outsider.

Much of the film is enclosed in tight spaces, emotionally charged and reactive as the stagecoach bounces from one plot point to the next. Ford films in Death Valley where the fractured plateaus are like broken teeth, an alien landscape that diminishes these trifling human anxieties. The ambush sequence utilizes many trucking shots and it’s difficult not to notice the tire tracks that criss cross the desert. Ford introduces John Wayne (as the Ringo Kid) with one of the most famous tracking shots ever: it’s so quick that the image slips slightly out of focus as it zooms in for a close-up!

Ford evokes the classic Western conventions before subverting them, showing the loners as the true heroes and the businessmen as thieves. Immorality gets its due as Hatfield and Gatewood face their own poetic justice, and the two lovers are given a well earned second chance. Ford sets up the climactic gunfight between Ringo and the Plummer clan then cuts away: he doesn’t show the battle but heightens tension as Dallas waits in the forlorn darkness. Together, they make a break for their own Nirvana as the Sheriff looks on knowing the law has been broken but Justice has been served.

Final Grade: (A)

Ford pulls focus to create a claustrophobic suspense between the characters, divided by their social graces (or lack thereof) and reputations. Dallas is a prostitute spurned by Lucy, pregnant with desire to visit her husband. Doc Boone’s soul is captured in a bottle of spirits, and he takes full advantage of Peacock the meek whiskey salesman. Hatfield is a rogue and gambler, offering his flirtatious protection to Lucy while the banker Gatewood jealously guards his suitcase and prejudices. Their fate clashes with the notorious Ringo Kid who surrenders uneventfully and forms a kinship with Dallas, the other outsider.

Much of the film is enclosed in tight spaces, emotionally charged and reactive as the stagecoach bounces from one plot point to the next. Ford films in Death Valley where the fractured plateaus are like broken teeth, an alien landscape that diminishes these trifling human anxieties. The ambush sequence utilizes many trucking shots and it’s difficult not to notice the tire tracks that criss cross the desert. Ford introduces John Wayne (as the Ringo Kid) with one of the most famous tracking shots ever: it’s so quick that the image slips slightly out of focus as it zooms in for a close-up!

Ford evokes the classic Western conventions before subverting them, showing the loners as the true heroes and the businessmen as thieves. Immorality gets its due as Hatfield and Gatewood face their own poetic justice, and the two lovers are given a well earned second chance. Ford sets up the climactic gunfight between Ringo and the Plummer clan then cuts away: he doesn’t show the battle but heightens tension as Dallas waits in the forlorn darkness. Together, they make a break for their own Nirvana as the Sheriff looks on knowing the law has been broken but Justice has been served.

Final Grade: (A)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)